The Bronze Lion – Bronzen Leeuw (BL) – is the 2nd highest Gallantry decoration of the Netherlands. It was instituted in 1944 and was the final part of the renewal of the Dutch system of gallantry decorations to extend beyond the Miltary Order of William, which remained the highest gallantry decoration.

Between 1944 and 1962 the Bronze Lion was awarded 1206 times. Most of these were for actions in WW2 (also retroactive for actions starting in 1940) and the colonial war in Indonesia in the period from 1945 to 1950. More recently it has been awarded several times for actions in Afghanistan.

In total 336 awards were to allied WW2 men and 869 to Dutch of which 177 were postumously awarded. A total of 176 were awarded to members of the Dutch East Indies Army.

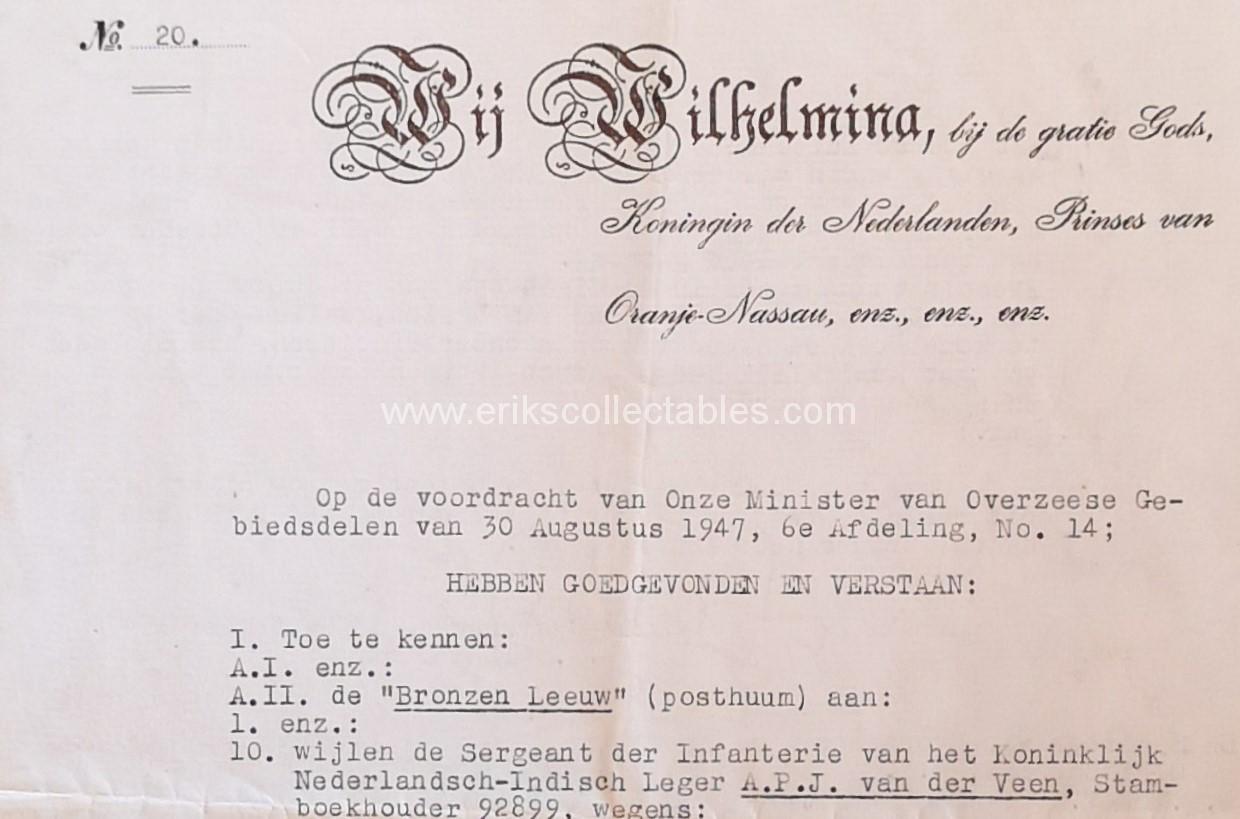

The documents here are for a posthumously awarded Bronze Lion to a sergeant of the infantry of the Dutch East Indies Army. The Bronze Lion and papers were sent to the father of the sergeant without any ceremony.

I am still researching the circumstances and hope to find more info on this resistance/guerilla group but here the info I have accumulated so far.

First the accompanying letter to the father which makes this a rare paper group!

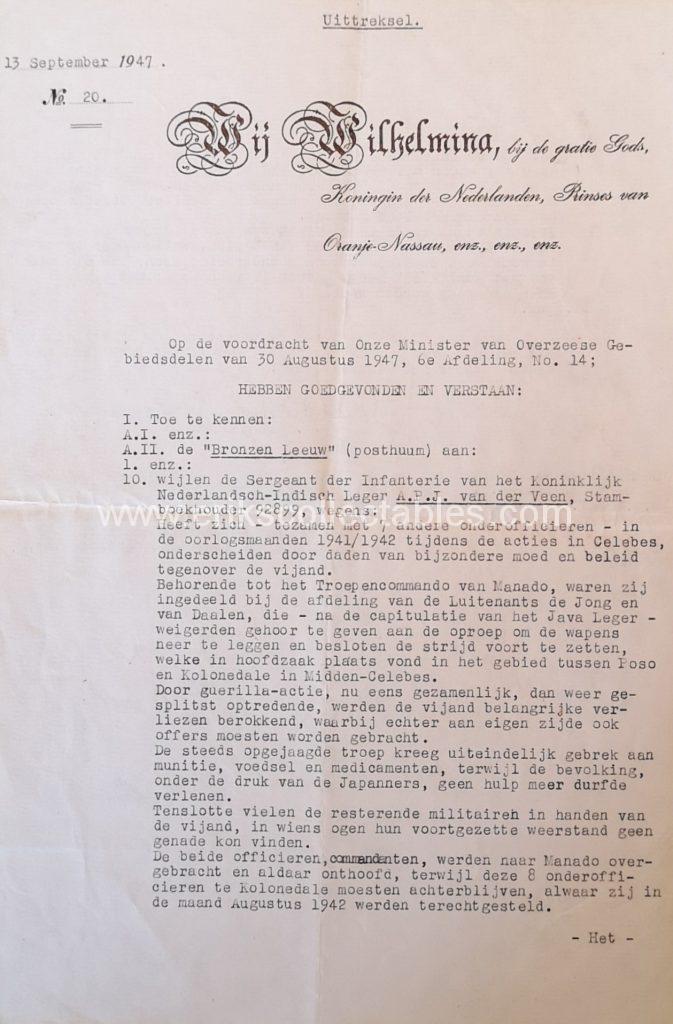

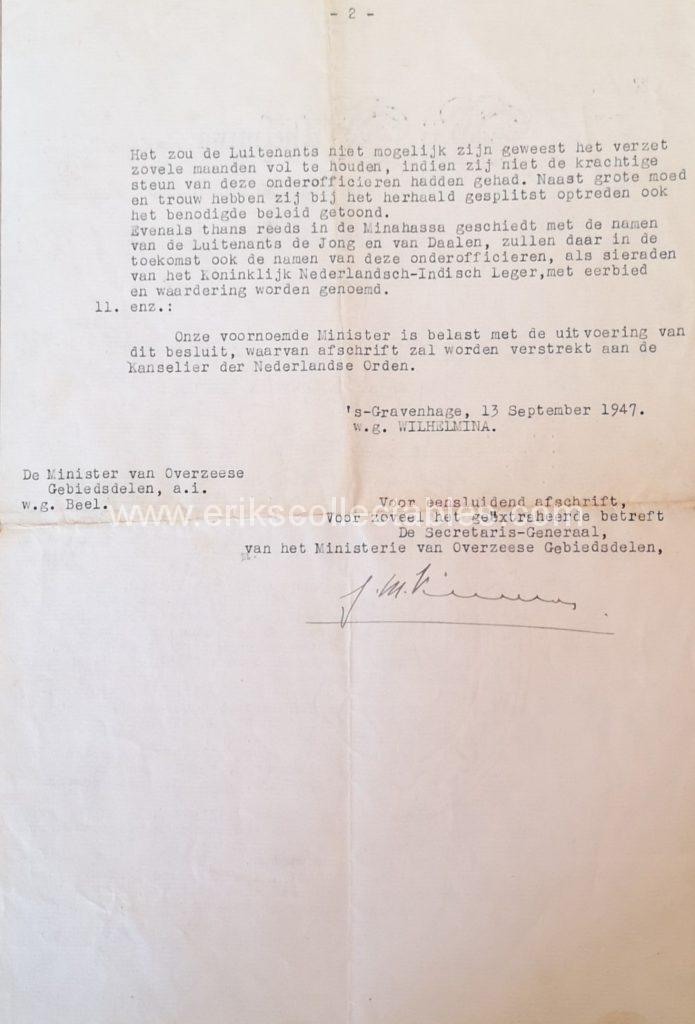

And below the two pages of the award document including the full citation:

Citation. See for the full text in Dutch farther below. It states that the awardee sergeant A.P.J. van der Veen was awarded the BL for his guerilla actions on the island of Celebes after the Japanese invasion (and following Dutch surrender) together with 7 other NCO’s and 2 officers. They participated in actions as a group but also split into several smaller groups led by the two officers. After some time they had no ammunition and food supplies left and fell into the hands of the Japanese. The Japanese showed no mercy for the continuation of guerilla actions after the main force had already surrendered. All 10 men were executed in August 1942 by the Japanese but on different dates and locations.

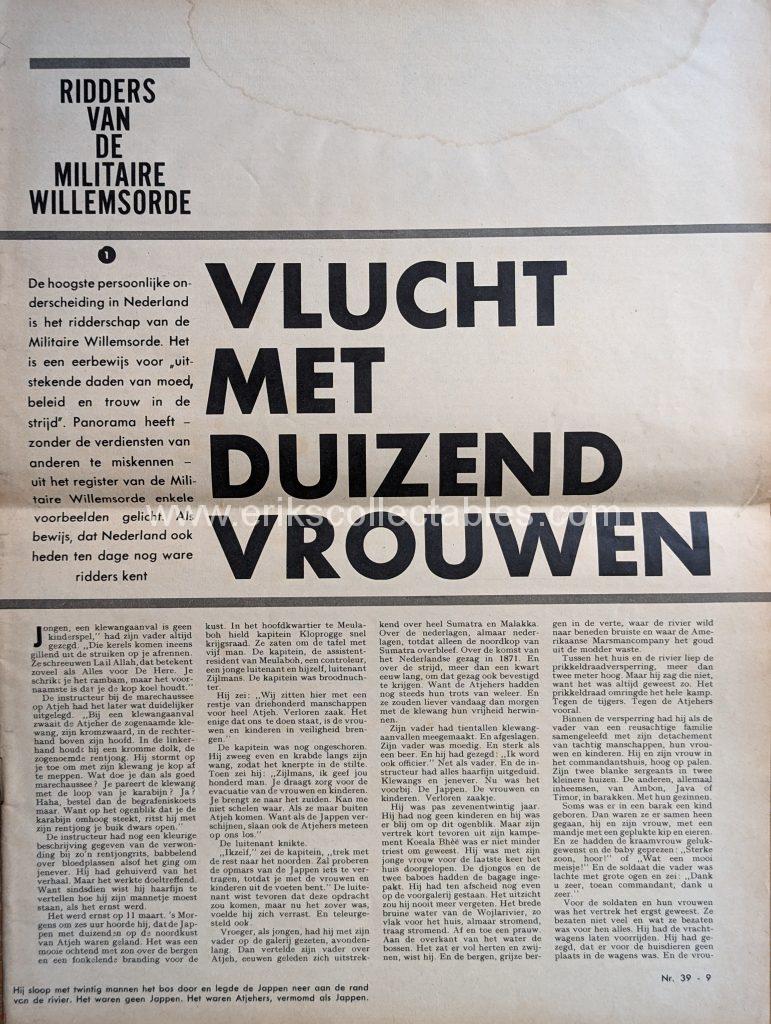

The following newspaper article from 1985 sheds some more light on the guerilla group on the island of Celebes:

Here is a translated summary of the text above:

The total group initially consisted of some 120 men. Lt Van Daalen already was in the process of surrendering his weapons after the main force on Java had surrendered in the beginning of March. Lt De Jong took action and stopped him, retook the guns that already had been handed in and freed the Dutch Prisoners of War from the Japanese force of some 50 men. The 120 men were split into several smaller groups all trying to survive and fight the Japanese. Without modern means of communication they kept in contact through couriers only. They did have some radiocommucation with the Dutch forces in Australia where they requested additional supplies and guns. These were delivered some five weeks later by the Australian Air Force, unfortunately the communication was also noticed by the Japanese. Based on that they sent 500 men of additional forces to the region. The Japanese were able to capture the dropped supplies.

In the beginning of August, after 5 months of fighting guerilla actions all supplies and ammunition were gone. The Japanese pressure on local people to hand over the guerilla’s was also intensified in that period. Based on these circumstances maintaining the group as a whole was no longer possible. Lt De Jong decided to give all remaining men the freedom to act as they saw fit. Surrender to the Japanese, try to hide or continue to fight as he and Lt Van Daalen and some 14 men did. After a few more days Lt De Jong and Lt Van Daalen and their men all were captured. All captured men were beheaded for their actions.

One sergeant that had chosen to go into hiding was able to stay out of the hands of the Japanese during the entire war and was the only known survivor of the group. He received no gallantry award! The faith of many of the others remains unknown/unresearched.

The commanding officer Lt De Jong was awarded the Military Order of William 4th class – the highest decoration for Gallantry. The other officer Van Daalen and 7 NCO’s were all awarded a Bronze Lion.

Lt Van Daalen was awarded the Bronze Lion before the awards to the NCO group. His text is different from that of the NCO’s but also different to that of the MWO. His award was made on January 27th 1947.

The NCO’s of the group received the Bronze Lion more than half a year later, on September 13th 1947. What the reason is for the difference remains unclear, but the size of the group probably influenced this and maybe the research into all men of this group.

Lt De Jong was awarded the MWO on October 7th 1947. That award process is the most difficult one to complete so that it was awarded later makes sense.

573 The late Willem Hendrik Johannes Everhardus van Daalen, born Batavia September 6th 1914, first lieutenant of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army, passed away, Sario-Menado August 25th 1942.

So far I have not been able to determine why the 8th NCO that is mentioned in the citation was not awarded a Bronze Lion. My hypothesis is that he was an indigenous soldier of whom the authorities have not been able to determine enough details or even a name. Probably similar to BL 653 to Sergeant Malawan of whom no other details are given. Not even his Army number has been traced.

Here is a list of the group of Bronze Lions, all with the same citation text:

650 The late Johannes Antonius Gerissen, born Nijmegen April th 1909, sergeant-major-instructor of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (army number 87021), passed away Kolonodale, August 15th 1942.

651 The late Nicolaas Christianus Antonius de Jager, born Leeuwarden August 8th 1905, sergeant-major-administrator of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (army number 85463), passed away, Kolonodale 14 aug. 1942.

652 The late Cornelis Wouter Kors, born Djokjakarta July 11th 1908, quartermaster of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (army number 84598), passed away Kolonodale August 15th 1942.

653 The late Malawan, sergeant of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army, passed away Kolonodale August 28th 1942.

654 The late Teunis Gijsbertus Onwezen, born Amersfoort November 5th 1908, sergeant of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (army number 86235), passed away Kolonodale August 15th 1942.

657 The late Arnoldus Petrus Johannes van der Veen, born Batavia March 20th 1919, sergeant of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (army number 92899), passed away Kolonodale August 12th 1942.

659 The late Hendrik Wonnink, born Soerabaja 23 juli 1914, sergeant of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (army number 92361), passed away Kolonodale August 12th 1942.

Through the website of the Dutch War Grave society it is also possible to search on location. The location Kolonodale shows two more victims in the same period. Soldier Cornelis Reijnhout born in Middelburg March 29th 1914 and sergeant Johannes Hendrik de Bruin born in Djokjakarta October 8th 1903. Both passed away on the same date as sergeants Wonnink, Van der Veen but did not receive gallantry awards. If they belonged to the same group (my current hypothesis) still has to be researched.

And the last award for this action is to the commanding officer of the group who was awarded the Military Order of William on Ocotber 7th 1947

5591 The late Johannes Adrianus de Jong, born 17-7-1914 Rotterdam, son of Frederik Willem and Aleida Suijkerbuik, passed away 25-8-1942 Sario.

They shall not be forgotten!

Full text of the citation in Dutch:

Wijlen Arnoldus Petrus

Johannes van der Veen, geb. Batavia 20 maart 1919, sergeant der infanterie van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Indisch Leger (stamboeknummer 92899), overl. Kolonodale 12 aug. 1942.

Heeft zich – tezamen met 7 andere onderofficieren – in de oorlogsmaanden 1941/1942 tijdens de acties in Celebes, onderscheiden door daden van bijzondere moed en beleid tegenover de vijand.

Behorende tot het Troepencommando van Menado, waren zij ingedeeld bij de afdelingen van de Luitenants de Jong en van Daalen, die – na de capitulatie van het Java Leger – weigerden gehoor te geven aan de oproep om de wapens neer te leggen en besloten de strijd voort te zetten, welke in hoofdzaak plaats vond in het gebied tussen Poso en Kolonodale in Midden-Celebes.

Door guerilla-actie, nu eens gezamenlijk, dan weer gesplitst optredende, werden de vijand belangrijke verliezen berokkend, waarbij echter aan eigen zijde ook offers moesten worden gebracht.

De steeds opgejaagde troep kreeg uiteindelijk gebrek aan munitie, voedsel en medicamenten, terwijl de bevolking, onder druk van de Japanners, geen hulp meer durfde verlenen.

Tenslotte vielen de resterende militairen in handen van de vijand, in wiens ogen hun voortgezette weerstand geen genade kon vinden.

De beide officieren, commandanten, werden naar Menado overgebracht en aldaar onthoofd, terwijl deze 8 onderofficieren te Kolonodale moesten achterblijven, alwaar zijn in de maand Augustus 1942 werden terechtgesteld.

Het zou de Luitenants niet mogelijk zijn geweest het verzet zovele maanden vol te houden, indien zij niet de krachtige steun van deze onderofficieren hadden gehad. Naast grote moed en trouw hebben zij bij het herhaald gesplitst optreden ook het benodigde beleid getoond.

Evenals thans reeds in Minehassa geschiedt met de namen van de Luitenants de Jong en van Daalen zullen daar in de toekomst ook de namen van deze onderofficieren als sieraden van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Indisch Leger met eerbied en waardering worden genoemd.