As a collector you sometimes get to be the custodian of a special and rare piece of history. Years ago I was able to acquire a post 1940 Knights Diploma for a Military Order of William 4th class. As the decoration itself is not named the paperwork is the most historically important part of the award to me as a researcher.

The Military Order of William is the highest Dutch award for bravery and has been awarded only 196 times since 1940 of which 55 awards were posthumous and 9 to units. Currently there are 4 living awardees, one from world war 2 and three recent awardees for actions in Afghanistan with our Special Forces (one of them a Helicopter Pilot for these forces). Most of these awards are for bravery in direct actions against the enemy but this is a very different story and therefore even more special, it is the story of saving 3000 civilians, mainly women and children from harm’s way….

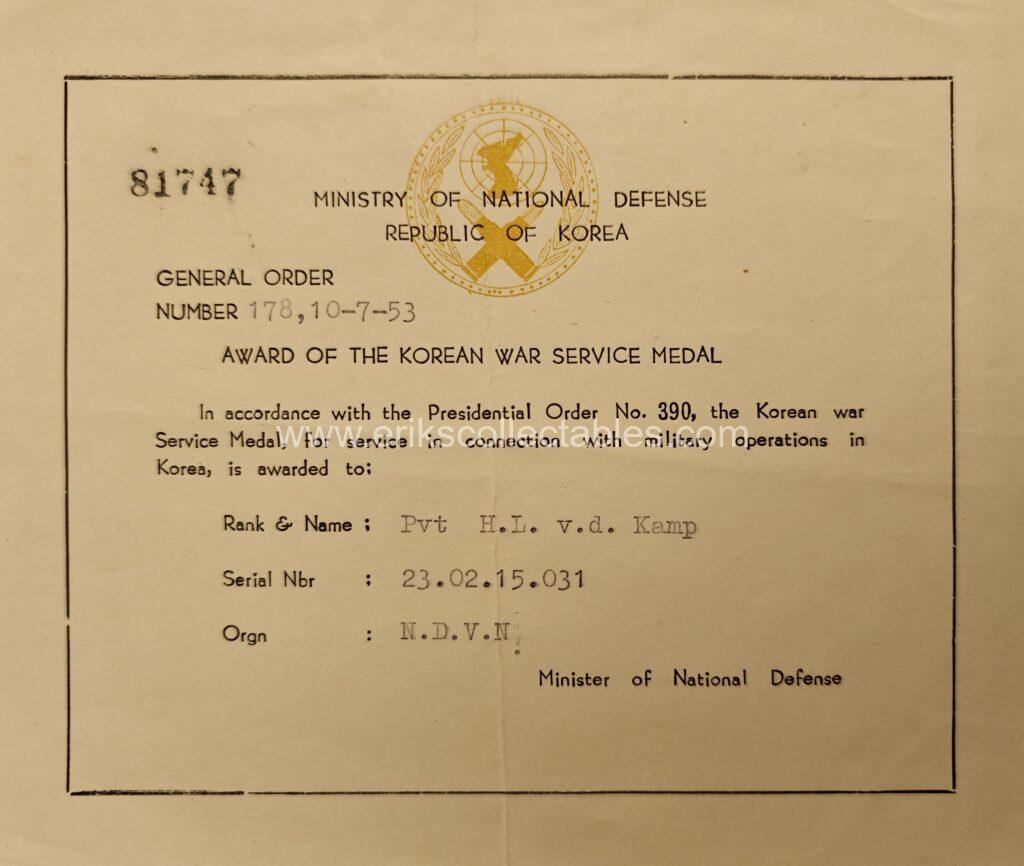

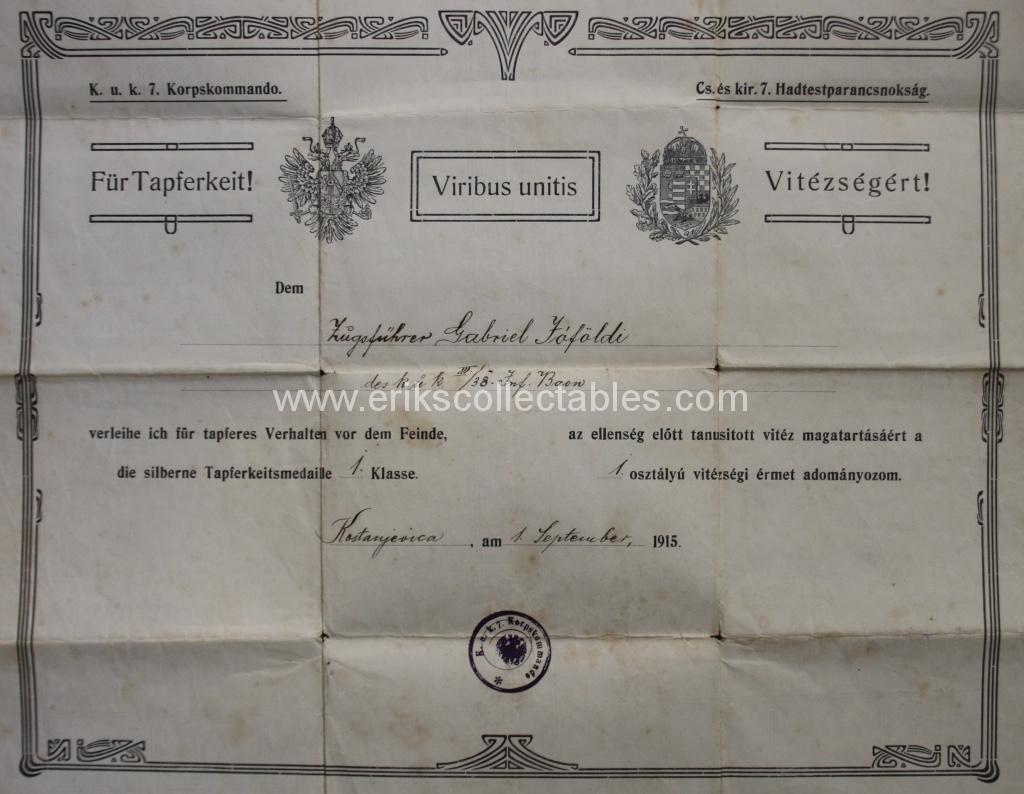

This is the citation of Adriaan Zijlman’s Miltary Order of William 4th class as seen on his Knights Diploma:

Translated:

Has distinguished himself in action by the perpetration of excellent deeds of bravery, good conduct and loyalty with his activities, under very difficult circumstances, as commander of a detachment of the 2nd Marechaussee division in February and March 1942 om the West Coast of Atjeh.

For the realisation of his assignment to evacuate ± 3000 women and children, mainly of local military forces on the west coast of Atjeh, he has taken the necessary actions in a discreet and dauntless way, also successfully facing several attacks by gangs of Acehnese and on March 19th 1942 breaking up a large gang of Acehnese in the surrounding of Tapa Toean. Until the surrender to the Japanese he has protected these women and children in an effective way against harm from Acehnese gangs.

It is a forgotten history that I hope to revive here with some context. Adriaan Zijlmans was born in the Dutch East Indies in 1914 in a place called Sigli which is in the North of the island of Sumatra. This region was called Atjeh then and currently it is known as Aceh. During the Dutch colonization of the East Indies this region never stopped the fight against the Dutch rule which was viewed by them as a religious duty as much as patriotic.

The war in Aceh started in 1873 for the Dutch and it never really ended until they left the region in 1950. The period between 1910 and 1942 was relatively peaceful considering the earlier wars. This changed in the early 1940s. The Japanese expansionism was seen as a sign of the dwindling might of the western colonizers and the rise of Asian strength. This revived the will to fight again in the Aceh region. The waiting in Atjeh was for an action of Japan against the colonies to start the uprising (again).

The fighting in the Atjeh region was so intense that an elite unit was developed: the Marechaussee (on foot). This unit was started in 1890 as an active counter guerilla unit against the local guerilla units. They moved on foot, were self-supporting and could go on patrols lasting several weeks and even up to months. From the beginning they were a mixed unit with both Asian and Western and even African soldiers with officers mainly being Dutch or of mixed Asian / Dutch descend (which were also considered Dutch in the army). Only the best infantry officers and men were selected for the unit. Especially in the 1920s and 1930s a placement there was seen as a good career move for officers and as a sign of being an extraordinary good field officer.

Zijlmans in front of his troops, 1940 – source NIMH

Adriaan Zijlmans was a Marechaussee officer in 1942 during the Japanese invasion. His father had already been an instructor in this unit so it was an honor to be in that unit as well, especially as an officer of mixed descend. In 1935 he had become an officer and was promoted to lieutenant 1st class in 1938. In 1942 he was the commander of the Marechaussee detachment in Koeala Bhee on the west coast of Atjeh. On December 8th war was declared against the Japanese. Many units already had been moved from Sumatra to Java for the defense of this main island of the colony. The amount of soldiers that was left on Sumatra was minimal, not even enough to withstand the now expected local uprising. And on February 23rd of 1942 that uprising started with the killing of a government official. This was shortly after the fall of Malaya. Java the colonies main island and primary target fell on March 8th 1942 opening the way for the Japanese to come to Sumatra which had not been attacked yet.

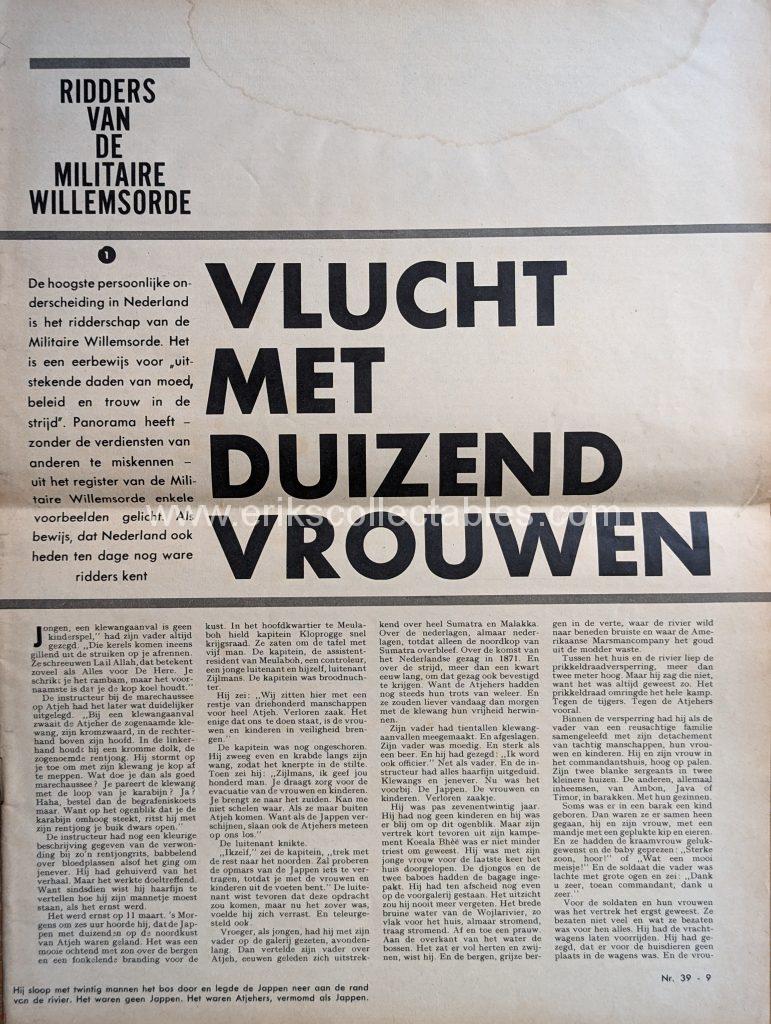

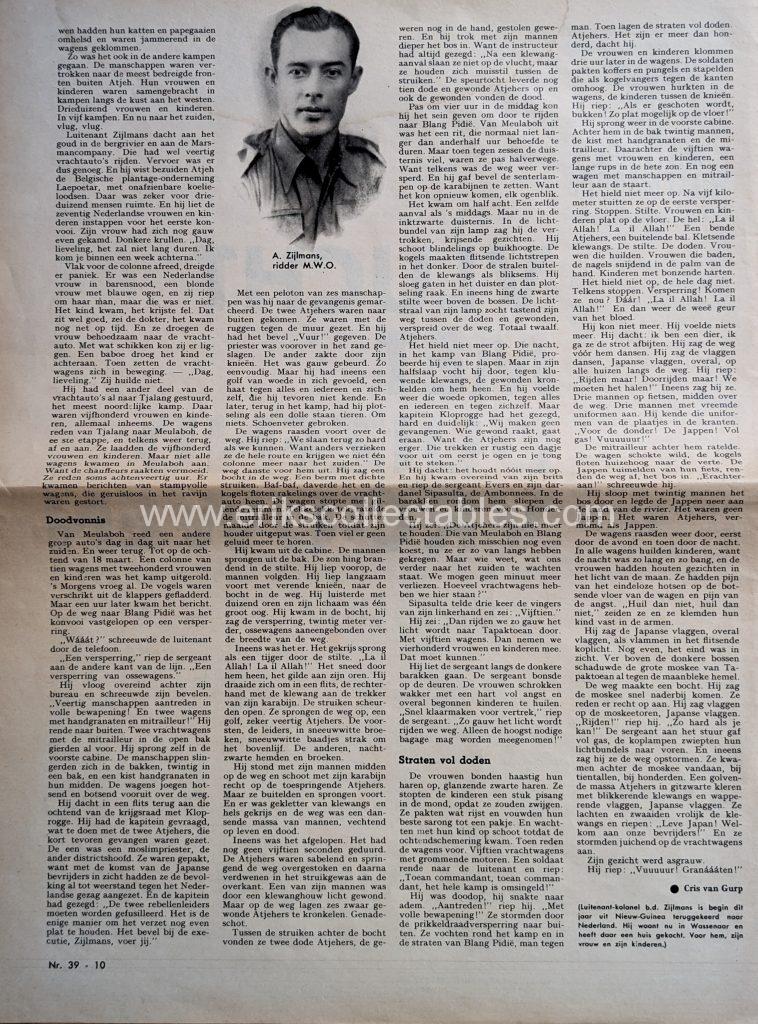

Publication about Zijlmans action from probably 1963, source unknown

Safety for the 3000 women and children and other civilians part of the local war plan. These civilians were mainly the women and children of the military forces and they were seen as an easy target by the local guerilla with a lot of emotional impact on the forces. Therefore, after the start of the uprising, all the civilians had already been gathered on the west coast of Atjeh to protect them with military force. With the start of the invasion of the Japanese on Sumatra is was necessary to assess the situation again as the forces were now needed against the Japanese as well. The assessment was done during an officers war council on March 15th 1942. The following goals were defined for the remaining armed forces in the Atjeh region:

- To engage the Japanese forces directly and actively as long as possible.

- To transport all civilians south, outside of the Atjeh region as their safety could no longer be guaranteed by the available forces.

- To cover for this retreat by continuous defensive fighting against the Japanese forces.

- After the civilians are outside of the Atjeh region to transport them further to relative safety from war actions to a corporation in Groot Singkel in mid Sumatra.

- Start a Guerrilla against the Japanese to harm their actions with the limited forces still available after the previous goals have been reached.

The start of a long and dangerous transport to safety for the civilians. Zijlmans received the responsibility for goals 2 and 4. A total of 15 lorries and multiple cars were available to transport the total of 3000 civilians 600 km to the south. One trip took up to 48 hours and the vehicles took app 400 people in one trip. It turned out to be very long, difficult and also dangerous trips. Several times a trip was hindered and stopped by attacks of local guerilla’s as described in the citation. All these were countered without any casualties to the civilians. During the time it took to complete all trips the Acehnese became more and more hostile towards the outsiders and they became more dangerous for the passengers and their military hosts. Several of the attackers were killed in the process. At the end all civilians were delivered safely to their destination and saw the end of the hostilities against the Japanese there.

Zijlmans became a prisoner of war of the Japanese. On March 23rd all Dutch troops formally surrendered. A small group of men continued with a guerilla but most of them were captured or killed in the year following. As part of his assignment to protect the civilians he also had to surrender himself to the Japanese.

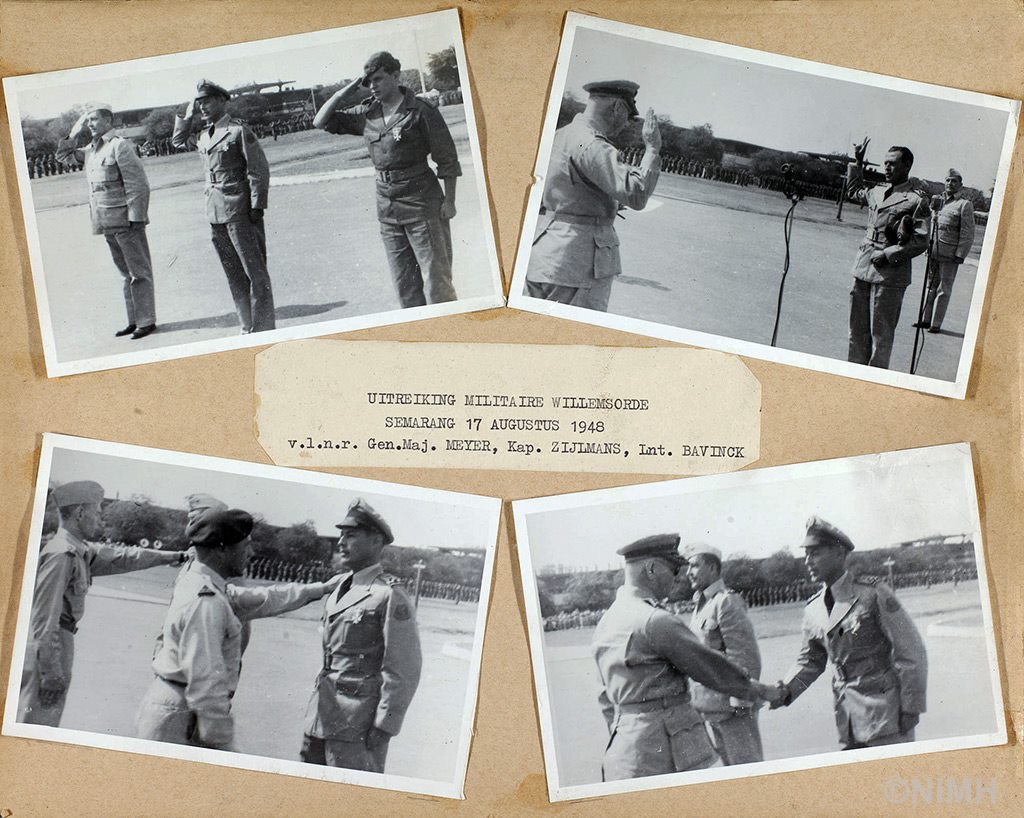

After his liberation in 1945 the continued to serve in the army receiving the Military Order of William on May 18th 1948. The Marechaussee were not reinstalled after the war so this was their last official action with Zijlmans becoming the last Marechaussee to receive this decoration and also the last citation with Atjeh as location which had been one of the most common locations in the last half of the 19th century.

After his return to the Netherlands in 1950 he continued to serve and rose to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in 1958 and got his honorable discharge in 1963. Until he passed away in 1992 he lived in Wassenaar. After his wife also passed away the Diploma came in my custody.

In 1948 he wrote an article about the impact of sleep deprevation on troops. That was before he received the award but is based on the same action. That period and the road trips were so intense and with so much stress and actual fighting that soldiers hardly slept and even started hallucinating in the process of saving the civilians.

Photos of the award ceremony by General Spoor in 1948

Source: NIMH

Decorations:

- Militaire Willemsorde 4e klasse

- Oorlog Herinneringskruis met 2 gespen

- Kruis voor Trouwe Dienst officieren met cijfer 25

Sources:

- De Militaire Willems-Orde sedert 1940, door P.G.H. Maalderink, 1982

- Tijdschrift de “Militaire Spectator” van Augustus 1948

- “Atjeh en de oorlog met Japan”, door Dr Piekaar, 1948

- Nationaal Archief

- NIMH

- Unknown magazine, 1963 – article about Zijlmans action